|

|

| This Web Site is dedicated to the Memories & Spirit of the Game as only Ken Aston could teach it... |

| Enjoy, your journey here on... KenAston.org |

| Ken Aston Referee Society ~ Football Encyclopedia Bible |

|

Herbert Chapman Administrators and Managers

|

||

| Source - References | ||

|

||

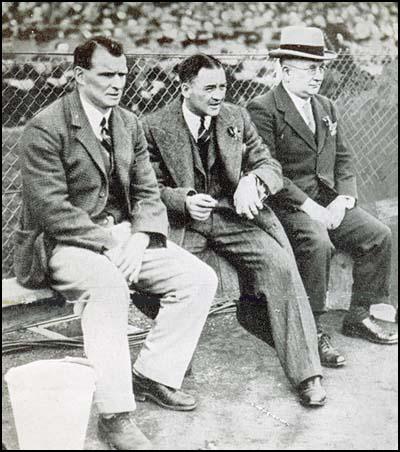

Jack Butler and Tom Parker watch Dan Lewis letting the ball slip under his body. |

||

|

Soon afterwards, Arsenal had a great chance to draw level. As Charlie

Buchan later explained: "Outside-left Sid Hoar sent across a long, high

centre. Tom Farquharson, Cardiff goalkeeper, rushed out to meet the

danger. The ball dropped just beside the penalty spot and bounced high

above his outstretched fingers. Jimmy Brain and I rushed forward

together to head the ball into the empty goal. At the last moment Jimmy

left it to me. I unfortunately left it to him. Between us, we missed the

golden opportunity of the game." Arsenal had no more chances after that

and therefore Cardiff City won the game 1-0. After the game Dan Lewis was so upset that his mistake had cost Arsenal the FA Cup that he threw away his loser's medal. It was retrieved by Bob John who suggested that the team would win him a winning medal the following season. Herbert Chapman believed that Lewis was the best goalkeeper at the club and he retained his place in the team the following season. On 2nd February, 1927, Arsenal played in a 4th round FA Cup tie against Port Vale. According to Tom Whittaker: "Arsenal were pressing hard, but things were not going just right and old George Hardy's eyes spotted something he felt could be corrected to help the attack. During the next lull in the game he hopped to the touchline, and cupping his hands, yelled out that one of the forwards was to play a little farther up field." Chapman was furious and sent Hardy to the dressing-room. On the following Monday morning Herbert Chapman summoned Tom Whittaker to his office and told him that he was now the first-team trainer. Chapman added: "I am going to make this the greatest club ground in the world, and I am going to make you the greatest trainer in the game." In October 1927, Herbert Chapman signed Eddie Hapgood, a 19 year old milkman, who was playing for non-league Kettering Town for a fee of £750. In his autobiography Hapgood describes his first meeting with Chapman: "Well, young man, do you smoke or drink?" Rather startled, I said, "No, sir." "Good," he answered. "Would you like to sign for Arsenal" Eddie Hapgood only weighed 9 stones 6 pounds at the time and as Tom Whittaker, the Arsenal trainer, pointed out: "Hapgood used to cause a lot of worry by frequently being knocked out when heading the ball." Whittaker later recalled: "All sorts of reasons were propounded as to why this should happen, but eventually I spotted the cause. Eddie was too light, and we had to build him up. At that time he was a vegetarian, but I decided he should eat meat." Bob Wall, Chapman's administrative assistant, wrote in his autobiography, Arsenal from the Heart: "He (Hapgood) played his football in a calm, authoritative way and he would analyze a game in the same quiet, clear-cut manner. Eddie set Arsenal players the highest possible example in technical skill and personal behavior." Hapgood made his debut against Birmingham City on 19th November 1927. It was not long before he was the club's regular left-back. As Jeff Harris pointed out in his book, Arsenal Who's Who: "Hapgood's many splendid attributes included, being technically exceptional, he showed shrewd anticipation and he was elegant, polished, unruffled and calm." In 1927 the Daily Mail reported that Henry Norris had made under-the-counter payments to Sunderland's Charlie Buchan as an incentive for him to join Arsenal in 1925. The Football Association began an investigation of Norris and discovered that he had used Arsenal's expense accounts for personal use, and had obtained the proceeds of £125 from the sale of the team bus. Norris sued the newspaper and the FA for libel, but in February 1929 he lost his case. The FA now banned Norris from football for life. In August 1928 the Arsenal team wore numbers on their backs. Herbert Chapman believed that these numbers would speed up moves by helping players identify each other more quickly. The Football League disagreed with this innovation and immediately banned the club from doing this again. Chapman had to content himself by placing numbers on the back of his reserve team. Chapman became frustrated by the conservatism of the Football Association and the Football League. In an article in the Sunday Express he stated: "I appeal to the authorities to release the brake which they seem to delight in jamming on new ideas... as if wisdom is only to be found in the council chamber... I am impatient and intolerant of much that seems to me to be merely negative, if not actually destructive, legislation." Chapman added: "We owe it to the public that our games should be controlled with all the exactness that is possible." He therefore suggested the introduction of goal judges. He was also in favor of playing games at night. Chapman arranged for floodlights to be built into the West Stand but the Football Association refused permission for the club to use them for official matches. Bob Wall later wrote: "Chapman thought deeply about an infinite variety of subjects associated with the game. He possessed the gift of seeing ahead of his time. He was able to visualize how soccer could benefit from adopting ideas which, in their infancy, seemed to most other people to be merely the outpourings of an eccentric mind." Chapman was also in favor of bonding sessions with the players. He was probably the first manager to take his players on a golfing holiday. The team regularly went to Brighton where they played golf at the Dyke Club. As Stephen Studd pointed out in Herbert Chapman: Football Emperor (1981): "He (Chapman) set great store by what he regarded as the dignity of the athlete, treating his players as human beings instead of mere paid servants, which was how most other players were regarded elsewhere." Samuel Hill-Wood became the new chairman of Arsenal. He had made his fortune from the cotton industry in Derbyshire and had previously owned Glossop North End. Freed from the restraints placed on him by the former chairman, Herbert Chapman began to buy the best players available. In May 1928, he paid a four-figure sum for Charlie Jones, who had developed a great reputation playing for Wales. In October, 1928, he decided to pay a transfer fee of over £10,000 for David Jack. Sir Charles Clegg, president of the Football Association, immediately issued a statement claiming that no player in the world was worth that amount of money. Others thought that at 29 years old, Jack was past his best. However, Chapman later commented that the buying of Jack was "one of the best bargains I ever made". In May 1929 Herbert Chapman signed the 17 year old Cliff Bastin from Exeter City for £2,000. This was considered to be a huge sum to pay for a teenager who had only played in seventeen league games. Chapman had spotted Bastin in a game against Watford. Bastin did not initially want to leave Devon but was persuaded by Chapman's manner: "There was an aura of greatness about Chapman. I was impressed with him straight away. He possessed a cheery self-confidence, which communicated itself to those around him. This power of inspiration and the remarkable gift of foresight, which never seemed to desert him, were his greatest attributes." The following month Chapman purchased Alex James from Preston North End for a fee of £8,750. At the time, the Football League operated a maximum wage of £8 a week. However, other clubs like Arsenal had found ways around this problem. Chapman arranged for James to obtain a £250-a-year "sports demonstrator" job at Selfridges. It was also agreed that James would be paid for a weekly "ghosted" article for a London evening newspaper. Alex James had been a goal scoring inside-forward at Preston North End. However, Chapman wanted him to plat the role of link man in his system. James found it difficult to adapt to this role and Arsenal started the 1929-30 season badly. In a cup-tie against Chelsea Chapman dropped James from the team. Arsenal won the game and James was not recalled until he had convinced Chapman that he was willing to play the link man role. Chapman's team-talk took place on Friday morning. His administrative assistant Bob Wall remarked that he always told players: "Never mind what the other team does - this is what you are going to do." Chapman had a magnetic table marked out as a football field, with little toy players that could be moved around on it. Every player was encouraged to give his own views on the game taking place the following day. By the end of the meeting every player was fully aware of the role they were to play in the match. As the Daily Mail pointed out at the time: "Breaking down old traditions, he was the first club manager who set out methodically to organize the winning of matches." Frank Cole of the Daily Telegraph, wrote: "If you sat near him (Chapman) at a big match... you realized the intense earnestness of the man. His face would go ashen grey as he lived every moment of the play. And when things were going against his men he seemed to be suffering mental agonies. I have never seen such concentration." Herbert Chapman gradually adapted the "WM" formation that he had introduced when he first came to the club. Herbert Roberts was the centre-half who stayed in the penalty area to break down opposing attacks. Chapman used his full-backs, Eddie Hapgood and Tom Parker, to mark the wingers. This job had previously been done by the wing-halves, who now concentrated on looking after the inside-forwards. Bob John and Alf Baker were the men he used in these positions. Dan Lewis was the goalkeeper in what became known as "defense-in-depth". The young George Male was often used if any of the full-backs or wing-halves were injured. Pulling the centre-half back left a gap in midfield and so Chapman needed a link man to pick up the ball from defense and to pass it on quickly to the attackers. This was the job of Alex James, who had the ability to make accurate long low passes to goal scoring forwards like David Jack, Jimmy Brain, Joe Hulme, Charlie Jones, Cliff Bastin and Jack Lambert. Chapman told the other forwards to go fast, like "flying columns" and if possible to make for goal direct. Chapman pointed out: "Although I do not suggest that the Arsenal team go on the defensive even for tactical purposes, I think it may be said that some of their best scoring chances have come when they have been driven back and then have broken away to strike suddenly and swiftly." He added "the quicker you get to your opponent's goal the less obstacles you find". Chapman also rarely made changes to the team. Even when individual players were in poor form he was reluctant to drop them. According to Chapman it was a matter of confidence and he saw it as his job to build up self-belief in his players. That is why he always criticized supporters if they barracked one of his players. "When they (team changes) are necessary I try to arrange that they cause as little disturbance as possible." Drastic changes only unsettled the players and if the side was not playing well, "the moderate course is always the best". Jack Lambert was one of the players who was often barracked by the Highbury crowd. Herbert Chapman was furious and proposed that barrackers should be thrown out of the ground if they did not respond to an appeal for fairness over the loud-speaker." Chapman later admitted that Arsenal crowd destroyed the confidence of one young player. The 20 year-old player told Chapman: "I'm no use to anyone in football and I had better get out. The crowd are always getting at me... I hope I shall never kick a ball again." Chapman eventually allowed the young man to leave the club "though it meant sacrificing a player who, I was convinced, had exceptional possibilities of development". Success was not immediate and Arsenal finished in 14th place in the 1929-30 season. They did much better in the FA Cup. Arsenal beat Birmingham City (1-0), Middlesbrough (2-0), West Ham United (3-0) and Hull City (1-0) to reach the final against Chapman's old club, Huddersfield Town. Dan Lewis had played in six of the seven ties on the way to the final. However, Herbert Chapman took the controversial decision of dropping Lewis, the man who had cost Arsenal victory in the 1927 FA Cup Final, from the team. At the age of 18 years and 43 days, Cliff Bastin was the youngest player to appear in a final. Arsenal won the game 2-0 with goals from Alex James and Jack Lambert. Dan Lewis was devastated by Chapman's decision and asked for a transfer. He was sold to Gillingham and Chapman resigned Bill Harper, who had been playing in the United States for three years. Arsenal won their first five matches in the 1930-31 season and did not lose until the tenth game. Aston Villa took a narrow lead but in November, 1930, Arsenal beat them 5-2 at Highbury with Cliff Bastin and David Jack scoring twice and Jack Lambert once. Sheffield Wednesday now went on a good run and for a while had a narrow lead over Arsenal. However, a 2-0 win over Wednesday in March took them to the top of the league. This was followed by victories over Grimsby Town (9-1) and Leicester City (7-2). When Arsenal beat Liverpool 3-1 at Highbury they became the first southern club to win the First Division title. The Gunners won 28 games and lost only four and obtained 66 points, six more than the previous best total and seven more than their nearest rivals, Aston Villa. That season Arsenal won a percentage of 78.57 points available to them. This had been bettered twice before by Preston North End (1888-89) with 90.9 and Sunderland (1891-92) with 80.7. Jack Lambert was top-scorer with 38 goals. This included seven hat-tricks against Middlesbrough (home and away), Grimsby Town, Birmingham City, Bolton Wanderers, Leicester City and Sunderland. The veteran David Jack scored 31 goals in 35 games. Other important players in the team included Alex James, Cliff Bastin, Joe Hulme, Eddie Hapgood, Bob John, Jimmy Brain, Tom Parker, Bill Harper, Herbert Roberts, Charlie Jones, Alf Baker and George Male. Cliff Bastin later recalled: "This Arsenal team of 1930-31 was the finest eleven I ever played in. And, without hesitation, I include in that generalization international teams as well. Never before had there been such a team put out by any club." Chapman was always preparing for the future. A lot of energy went into producing a good reserve side. As Bernard Joy pointed out: "Chapman had intended to set up a strong second string when he came to Highbury and more convincing proof that he had succeeded when was the reserves came into the senior team." In the 1930-31 season the Arsenal reserve side won the Combination league title for the fifth year running. Frank Moss was playing in the reserves of Second Division side, Oldham Athletic, when Chapman, saw his potential and bought him for £3,000. He made his debut against Chelsea on 21st November 1931. He remained the first-team goalkeeper for the rest of the season. Arsenal began the season badly. West Bromwich Albion won at Highbury in the opening game and victory did not come until the fifth match, at home to Sunderland. Arsenal's main problem was a lack of goals from Jack Lambert who was suffering from an ankle injury. However, Lambert recovered his goal scoring touch and Arsenal went on a good run and gradually began to catch the leaders, Everton. Arsenal also did well in the FA Cup. They beat Plymouth Argyle (4-2), Portsmouth (2-0), Huddersfield Town (1-0), and Manchester City (1-0) to reach the final. Arsenal's league form was also good and after the FA semi-final they were only three points behind Everton, with a game in hand. This was followed by victories over Newcastle United and Derby County and it seemed that Arsenal might win the cup and league double. The next game was against West Ham United at Upton Park. After two minutes Jim Barrett went for a loose ball with Alex James. According to Bernard Joy: "James chased after it, both went awkwardly into the tackle and as James slipped, down came the full weight of Barrett's fifteen stone on to his outstretched leg." James had suffered serious ligament damage and was unable to play for the rest of the season. Arsenal missed their playmaker and won only one more league game and Everton won the title by two points. Arsenal played Newcastle United in the FA Cup Final on 23rd April, 1932. The Arsenal team that day was: Frank Moss, Tom Parker, Eddie Hapgood, Charlie Jones, Herbert Roberts, George Male, Joe Hulme, David Jack, Jack Lambert, Cliff Bastin and Bob John. Arsenal scored first, eleven minutes after the start, when John headed in a centre by Hulme. Just before half-time Jimmy Richardson chased what appeared to be a lost cause, when David Davidson sent a long ball up the right wing. When the ball appeared to bounce over the line, the Arsenal defence instictively relaxed. Richardson managed to hook the ball into the middle and Jack Allen was able to head home. Despite the protests, the referee W. P. Harper, awarded the goal. David Jack missed an easy chance midway through the second-half and soon afterwards Allen scored again to win the game for Newcastle United 2-1. At the beginning of the 1932-33 season Chapman changed Arsenal's kit. He replaced the lace-up jersey with a shirt with buttons at the neck and a turn-over collar. He also decided that the sleeves should now be white instead of red. The colour of the socks was altered to a more distinctive blue and white so that the players could recognize their colleagues more easily without looking up. |

||

Tom Whittaker, Alex James and Herbert Chapman watching the 1932 Cup Final. |

||

|

Arsenal was in great form in the 1932-33 season. They only lost two

matches against West Bromwich Albion and Aston Villa in their first 18

games. A 9-2 win over Sheffield United gave the club a six-point lead at

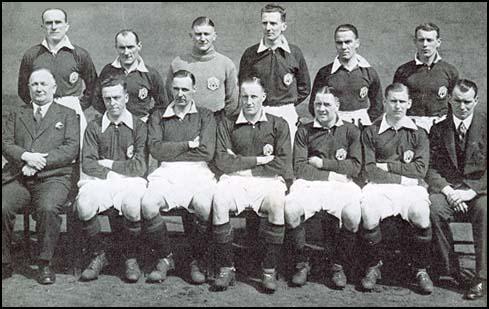

Christmas. Arsenal played Walsall of the Third Division North in the FA Cup on 14th January 1933. Injuries and illness robbed Arsenal of several key players including Eddie Hapgood, Joe Hulme, Jack Lambert and Bob John. Four inexperienced reserves were drafted into the side. They all performed badly and so did the regular members, with David Jack missing several opportunities to score. The tackling of the Walsall players, especially on Alex James and Cliff Bastin, also caused the team serious problems. As Bernard Joy pointed out: "They (Walsall) were aided by the narrow ground which was made more cramped by the encroachment of spectators up to the touchlines." Fifteen minutes after the interval, Gilbert Allsop headed in from a corner. Soon afterwards, Tommy Black, who was deputizing for Eddie Hapgood, gave away a penalty with a blatant foul on Bill Sheppard. Walsall scored from the spot and managed to hold out for a 2-0 win. It was the greatest giant-killing result in FA Cup history. Chapman was furious with Tommy Black because he had made several bad tackles on Bill Sheppard before giving away the penalty. Chapman set high standards of behavior on the field and Black's behavior was unforgivable. He was banned from Highbury and soon afterwards he was transferred to Plymouth Argyle. Arsenal recovered quickly from the defeat in the FA Cup and were unbeaten in the league until March. This included a 8-0 win over Blackburn Rovers. By the end of the season Arsenal was four points in front of Aston Villa. The Arsenal team in the 1932-33 season. Front (left to right): Tom Parker, Charlie Jones, Frank Moss, Herbie Roberts, Bob John and Tommy Black. Seated: Herbert Chapman, Joe Hulme, David Jack, Jack Lambert, Alex James, Cliff Bastin and Tom Whittaker. |

||

The Arsenal team in the 1932-33 season. Front (left to right): Tom Parker, Charlie Jones, Frank Moss, Herbie Roberts, Bob John and Tommy Black. Seated: Herbert Chapman, Joe Hulme, David Jack, Jack Lambert, Alex James, Cliff Bastin and Tom Whittaker. |

||

|

Joe Hulme, David Jack, Jack Lambert, Alex James, Cliff Bastin and Tom

Whittaker. Cliff Bastin, the team's left-winger, was top scorer with 33 goals. This was the highest total ever scored by a winger in a league season. Joe Hulme, the outside right, contributed 20 goals. This illustrates the effectiveness of Chapman's counter-attacking strategy. As the authors of The Official Illustrated History of Arsenal have pointed out: "In 1932-33 Bastin and Hulme scored 53 goals between them, perfect evidence that Arsenal did play the game very differently from their contemporaries, who tended to continue to rely on the wingers making goals for the centre-forward, rather than scoring themselves. By playing the wingers this way, Chapman was able to have one more man in midfield, and thus control the supply of the ball, primarily through Alex James." Jeff Harris argues in his book, Arsenal Who's Who: "The reason that Bastin was so deadly was that unlike any other winger, he stood at least ten yards in from the touch line so that his alert football brain could thrive on the brilliance of James threading through defence splitting passes with his lethal finishing completing the job." Matt Busby was playing for Manchester City at the time. He later recalled: "Alex James was the great creator from the middle. From an Arsenal rearguard action the ball would, seemingly inevitably, reach Alex. He would feint and leave two or three opponents sprawling or plodding in his wake before he released the ball, unerringly, to either the flying Joe Hulme, who would not even have to pause in his flight, or the absolutely devastating Cliff Bastin, who would take a couple of strides and whip the ball into the net. The number of goals created from rearguard beginnings by Alex James were the most significant factor in Arsenal's greatness." In March 1933, Herbert Chapman paid £4,500 for Ray Bowden. He was brought in to replace David Jack who was nearing the end of his career. The 1934-35 season started well with an 8-1 crushing of Liverpool. The first four home games produced 21 goals. The away form was poor but Arsenal built up an early lead in the First Division. |

||

|

||

|

On 1st January 1934 Herbert Chapman went to watch Notts County play Bury

as he was interested on one of their young players. The following day he

attended the game between Sheffield Wednesday and Birmingham City.

Wednesday were the visitors at Highbury on the following Saturday and

Chapman considered them to be Arsenal's main rivals for the league

championship. He developed a cold but insisted on watching Arsenal's

third team play on the Wednesday. The following day he was forced to

take to his bed and died of pneumonia on Saturday morning. Chapman was

buried at St Mary's in Hendon on 10th January 1934. David Jack, Eddie

Hapgood, Joe Hulme, Jack Lambert, Cliff Bastin and Alex James were the

six pallbearers. Herbert Chapman had been accused of buying success at Arsenal and they became known as the "Bank of England" club. However, between 1925 and 1934 Chapman had spent £101,000 in fees and received £40,000 for those he sold. A yearly average cost of £7,000. This was easily made up for in increased revenue from gate receipts. For example, in his final year as manager, the club made a profit of £35,000. |

||

| Source - References | ||

|

(1) Tom Whittaker, The Arsenal Story (1957) Among the many applications for what was regarded in soccer as a plum job, was one from Mr. Herbert Chapman, then holding a similar position with Huddersfield Town, champions of the First Division for the past two seasons. After an interview with the Arsenal directors in London he was given the job. Chapman did not keep to the contract implied in the advertisement during the nine years he ruled at Highbury before death for ever stilled that restless, electric, planning brain. He was to set up a new record fee for a transfer (David Jack); was to pay nearly £20,000 for two players (Jack and James), an amount many clubs hadn't spent in ten years in assembling the whole of their playing staff! He was to revitalize Arsenal, to change their style, to lay the foundation stones of their great successes, and to see many of the storey's of the House of Highbury built. His drive was going to impel the mighty London Passenger Transport Board to change the name of an Underground station from Gillespie Road to Arsenal; his training methods were to become the talk of the soccer world; his style of football is still played throughout Great Britain. Chapman instituted player-conferences, now copied by almost every club and national team throughout the world. He severed nearly every connection with pre-Chapman Arsenal, even altering the color scheme. He said nothing was too good for Arsenal, so bought up a special luxury train for the players to travel in; he introduced soccer to the speed and luxury of air travel. (2) Herbert Chapman, Herbert Chapman on Football (1935) I receive many letters during the season from supporters of the Arsenal suggesting ways and means by which the team might be improved. At least, they show a kindly interest in the fortunes of the club. One which arrived after four consecutive wins was startling. The proposal was that four of the players who had contributed to these successes should be dropped, and that their places should be taken by men from the reserves. The writer told me he lived at Felixstowe, and that he came every week to Highbury to see both the first and second teams. He was one of the regulars who took up their places in one of the corners of the ground, and after considering how the team might be improved, they had asked him to put their conclusions before me. Why the changes should be made had been reasoned out, and I was told how better results might be achieved. Drop four players! In all my experience of football management I cannot remember having made such sweeping changes in a side. I hate to have to make changes at all, and when they are necessary I try to arrange that they cause as little disturbance as possible. If I were to make four alterations in a team, unless they were due to circumstances over which I had no control, I should regard it as a confession that. I had been seriously at fault previously in judging the merits of the men. (3) Herbert Chapman, Herbert Chapman on Football (1935) The captain is the mouthpiece of the staff in their relationship with the management, and he has to ventilate any grievances his colleagues may have, even though he may not agree with them. His position on the field, too, is not always an enviable one. In an exciting moment I have seen him give an instruction to a colleague and, in front of the crowd, receive a hasty and very improper retort. How many players to-day have the essential personality and capacity to command? The captaincy of a first-class football team differs greatly from that of a golf club. The manager is in charge of the team all the week, with the trainer as his chief lieutenant, giving instructions as to the kind and the amount of work which has to be done in individual cases. Together, they are like a small sub-committee in charge of a Test Match team offering advice to the captain. But, in my judgment, the correct way to captain a side is not entirely through the appointed captain. My idea is that the whole team should share the responsibility. They should be trained to think not only for themselves but for the side generally, and they should be encouraged to express their views and offer suggestions for the improvement of the play. My endeavor is always to make the most of the brains of everyone. I shall never be too old to learn or to borrow the idea of some one else, if it is a good one. We at Highbury throw all our knowledge into a common pool, and the benefit is incalculable. During recent years I do not think there has been a finer captain than Jimmy Seed of Sheffield Wednesday. He took charge of the team when it seemed certain that they must go down to the Second Division, and they not only survived under his inspiring leadership, but became one of the best sides we have had since the war. His men had boundless faith in him. Such, in fact, was their faith in him, that they believed that nothing could go wrong while he was on the field. Charlie Buchan was another great captain, and I was sorry that he missed the highest honors while he was with the Arsenal. It should not be forgotten, however, that he led the side when they were runners-up for the championship, and also when they got into the Final of the Cup Competition. (4) Herbert Chapman, Herbert Chapman on Football (1935) Confidence! It is the greatest asset a man can possess. Look at Gallacher of Chelsea. The Scotsman starts in every match with abounding belief in himself. Who is there to beat him? He may lose the ball once in trying to break through, but he regards that simply as an accident, and he will carry out the same movement five minutes afterwards, just as certain that he will succeed. You will see the same kind of thing in the play of Alex James. He will hold the ball, to draw and fool an opponent, and possibly lose it. But he does not decide that he must not make a similar attempt again. Rather is he the more eager to try it. He believes he can do it, and even should he fail a second time, he is not at all upset. As a further illustration of what I mcan, take Herbert Sutcliffe at cricket. He may be beaten twice in an over, but he does not turn a hair. Or Wilfred Rhodes. He did not lose his length because a batsman had hit him for three consecutive 4's. He was more likely to get him with the next ball. I am convinced that 75 per cent. of players do not give half their full value because they lack confidence in themselves. They have not the courage to attempt the things which are well within their scope, and there is no doubt that spectators are largely responsible for this. The man who coined the phrase "Get rid of it" could have had no idea of the harm it would cause in the game generally, but it was a very unfortunate one, and I wish it might never be heard again. Rather should every encouragement be given to players to hold the ball, for only in this way can football be orderly and methodical. Not so long ago a young player told me that when he played in the second team the ball seemed as big as a balloon, and that he could do what he liked with it. In the senior side, however, it shrank to the size of a marble. (5) Herbert Chapman, Herbert Chapman on Football (1935) There is much unhappiness among footballers of which the public know nothing. I have sometimes thought that it would be better if they did, for it would give them a fuller understanding of many matters, and lead them to a fairer and more generous outlook on the game. For the football spectator can be, and often is, cruel. A player from the north once told me that the crowd on his ground had been "getting at him." "I know I've not been playing well," he said. "At the start of the season the ball never seemed to run right for me, and I couldn't do right. Now I'm playing worse than ever, because I'm thinking more about the crowd than the game. They're sure to drop me, and the next thing I'll be transferred, if anyone can be persuaded to take me. I'm fed up. I wish I had stuck to my job and never come into football." I should estimate the player's worth in terms of a transfer fee at not less than £3000, yet obviously he was perilously near the mark when he would be a dead loss to his club. Another incident which I recall points to the incalculable harm which the barracker may do. It was signing-on time some years ago. A youth came into the office, and I put the form before him to sign. To my amazement he covered his face with his hands and burst into tears. "It's no use," he said. "I'm no use to anyone in football and I had better get out. I can't stand it any longer. The crowd are always getting at me. I'm going home and I hope I shall never kick a ball again." At the age of twenty, and after two years as a professional, he was grief stricken, and he was a player of the highest promise. I knew that he had been barracked at times, but I did not realize that he was so sensitive. Unfortunately, he had hidden his feelings, and none of us knew how he had suffered. I persuaded him to re-sign, and he came back for the new season happily enough. Moreover, for a time he got on much better. But again the crowd turned against him, and I decided that it would be better if he left and made another start, though it meant sacrificing a player who, I was convinced, had exceptional possibilities of development. The truth was that he was too sensitive. No one expects the football crowd to be silent; we like them, in fact, to display their interest and enthusiasm. We do not object when they cheer the other side. Impartiality is good at all times. But we insist that the players should be treated fairly. We will not tolerate the noisy, vulgar barracker. I am persuaded to write of this matter not from what I have seen and heard, but from what I have been told. I have discussed it with two different sets of directors who have been troubled and perplexed by the nuisance, and I frankly stated that, in my opinion, it was then duty to protect their players. On one occasion a well-known man was persistently barracked in the Midlands, and from what I am told happened it is evident that he at last lost his temper. Turning to one conspicuously noisy spectator he shouted, "If you'll come round to the dressing-room at the finish, we'll settle it." Obviously, that sort of thing should not happen, and, in my opinion, if clubs gave their players proper protection, there would be little possibility of it. If the players and the public are to fall out, what is to he the result'? (6) Herbert Chapman, Herbert Chapman on Football (1935) I remember David Jack making his first appearance for the Arsenal, in a match at Newcastle. For days he had been boomed as the £10,000 footballer, and a natural fear had seized him that, if he were judged by his display on that occasion, it would be decided that his value had been grossly exaggerated. He knew, too, that the players of the Arsenal expected a great deal from him. He had come to take the place of Charlie Buchan, and as the man who was to restore the fortunes of the club. That match was a nightmare to Jack. He told me afterwards that he felt as if he had been thrown to the lions, and for some time afterwards he was rather unhappy, though properly proud of being the first player judged to be worth such a considerable fee. I doubt whether he has even got over it yet. In a confidential talk I had with him shortly before the 1930 Cup Final, he told me how anxious he was that we should win, in order that the club might think that his fee had been justified. If we had lost at Wembley, my opinion of Jack and his value to the Arsenal would not have changed in the slightest. I should still have thought that in securing him from Bolton Wanderers I had made the best bargain of my life. (7) Herbert Chapman, Herbert Chapman on Football (1935) It will he recalled, too, that Alex James had an unhappy experience in the early part of the same season, and I shall always think that the dead set which was made against him was deliberately manufactured to hurt the club as well as the player. It was one of the meanest things I have ever known, and one of the finest players it has been my pleasure to see almost had his heart broken. That is not an exaggeration. Like Jack, James was a much-boomed player when he joined us. In Scotland, where he was perhaps better known and appreciated than in England, though he had been nearly five years at Preston, he was known as "King James." He had his ideas as to how he should play, but they did not quite fit in with those we favoured, and it was necessary that he should make some change. He was always willing to do this, in fact, you could not wish for a better club man. However, before he had time to settle down to the Arsenal style, he was seriously upset by the bitter criticism to which he was subjected, and it was decided that the only thin- to do was to allow him a rest. I frankly admit, however, that I did not know how we were going to get him back into the side. It may be remembered how it was done, how he was taken to Birmingham, and brought out again in the replayed Cup tie with Birmingham. I am happy to say he has never looked back since, and that he has justified every hope and expectation. But the Arsenal nearly lost him, and if the worst had happened, those who had made the game a misery to him would have had to bear the blame. (8) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955) One day in May 1925, I was serving in my Sunderland shop, when the great Herbert Chapman walked in. A few weeks before, he had left Huddersfield Town to take over the managership of Arsenal. His first words on seeing me were: "I have come to sign you on for Arsenal." "Yes,' I replied, thinking he was joking, "shall we go into the back room and sign the forms?" "I'm serious," was his answer. "I want you to come with me to Highbury." "Have you spoken to Sunderland about it?" I asked, still thinking it was all part of the joke. "Oh, yes," said Mr Chapman. "If you don't believe me, ring up Bob Kyle, and he'll tell you." Still unbelieving, I phoned the Sunderland manager. "Yes," he said, "we have given Arsenal permission to approach you." "Do you want me to go?" I asked him. "We are leaving that to you," he said. "Do what you think best for yourself. It's in your hands." Slowly I put down the receiver. I was almost stunned by what I had heard. It had never crossed my mind that Sunderland would be prepared to part with me so easily. Mr. Chapman just said one word: "Well?" And all I could say at that moment was: "Give me time to think it over. Come back tomorrow, and I will let you know, one way or the other." When I went home that evening I talked the matter over with the family. The thing that hurt most was that, after more than fourteen years with Sunderland, my services were so lightly regarded. Finally I made up my mind. The next morning Mr. Chapman again called at the shop. I said to him: "I am prepared to sign for Arsenal, but I shan't do so until the end of July." "Will you give me your word you'll sign then?" he asked; and when I replied "Yes", we talked of other things. A lot of them concerned the Arsenal team and what I thought about them. A few weeks later, a Sunderland director, Mr. George Short, called on me at the shop. "What's this about your leaving Sunderland?" he asked. When I told him, he replied: "Then I shall resign." He kept his word. It seemed there were sharply divided opinions about my leaving, but the strange thing is that nobody asked me to change my mind. The summer went by, and then towards the end of July, Mr. Chapman again visited me in Sunderland to complete the negotiations. It was arranged that I should go to London to talk with the Arsenal chairman, Sir Henry Norris, and a director, Mr. William Hall. At the same time I was to look over houses similar to the one I had in Sunderland. As soon as the housing accommodation was settled - and that was not the difficult matter it is today - I met Mr. Chapman again to sign the necessary forms. Before doing so I asked him, as a matter of personal satisfaction, what was the transfer fee. After a little persuasion he gave me an answer. It was almost as big a shock as the transfer itself. He said: "Well, it's rather a peculiar one. We pay Sunderland cash down £2,000, and then we hand over £100 to them for every goal you score during your first season with Arsenal." (9) Bob Wall, Arsenal from the Heart (1969) I worked from 8.30 a.m. to 6.30 or 7 at night. My duties were handling Chapman's correspondence and also learning the work of the box-office under the assistant-manager, Joe Shaw." My official starting time in the morning was nine o'clock but Mr. Chapman expected his correspondence to be opened and ready for him when he walked into his office at nine. If it wasn't there, he wanted to know why. So, for my self-protection, I always reported 30 minutes early. No member of the staff was permitted to leave the building unless he had telephoned Chapman's office at six o'clock and enquired: 'Is it all right for me to go now, Mr. Chapman?' We all had a real respect for him. I suppose too, there was a tinge or more of fear in our approach to him. (10) Tom Whittaker, The Arsenal Story (1957) Among the many applications for what was regarded in soccer as a plum job, was one from Mr. Herbert Chapman, then holding a similar position with Huddersfield Town, champions of the First Division for the past two seasons. After an interview with the Arsenal directors in London he was given the job. Chapman did not keep to the contract implied in the advertisement during the nine years he ruled at Highbury before death for ever stilled that restless, electric, planning brain. He was to set up a new record fee for a transfer (David Jack); was to pay nearly £20,000 for two players (Jack and James), an amount many clubs hadn't spent in ten years in assembling the whole of their playing staff! He was to revitalize Arsenal, to change their style, to lay the foundation stones of their great successes, and to see many of the storeys of the House of Highbury built. His drive was going to impel the mighty London Passenger Transport Board to change the name of an Underground station from Gillespie Road to Arsenal; his training methods were to become the talk of the soccer world; his style of football is still played throughout Great Britain. Chapman instituted player-conferences, now copied by almost every club and national team throughout the world. He severed nearly every connection with pre-Chapman Arsenal, even altering the color scheme. He said nothing was too good for Arsenal, so bought up a special luxury train for the players to travel in; he introduced soccer to the speed and luxury of air travel. (11) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955) Within a few days of my arrival at Highbury, Mr. Chapman called a meeting of the players. I was appointed captain. Though I did not want the job - I thought I would be of greater service as one of the rank and file-they insisted I should be in charge on the field. One of the first things we did was to create a spirit of friendship among the whole staff. All were to be pals, working for the good of the club. We discussed matters from all sides, ironing out any bones of contention. We soon became hundred per cent Arsenal players. That, I think, is the secret of the team's unrivalled success over the years. The club comes first. Team-work is not allowed to suffer from petty squabbling. Weekly meetings were instituted. On the eve of every match, big or small, the players, manager and trainer, talked it over. We had no blackboards or plans of the field. It was a straightforward discussion, with every player airing his point of view. We talked over moves for every basic part of the game, such as throws-in, corner-kicks, free-kicks, and the strong and weak points of our own team, as well as the opposition. We soon knew what every player was expected to do. It was an accepted principle that we never discussed any move that the opposition could interfere with. We concentrated on our own side-covering, backing up, calling for the ball, and any point that we could work out for ourselves. Every player was made to talk. Some took a lot of persuading, but eventually all joined in, even the most self-conscious and the "silent ones". It was during the summer of 1925 that the change in the offside law was made. It was the biggest upheaval in the game for many years, and, in my opinion, altered it completely. It was necessary, though. There were so many full-backs copying the example of Bill McCracken, Newcastle and Irish international full-back, known as the "offside king", that the game was fast developing into a procession of free-kicks for offside. The change from three defenders to two between an attacker and the goal brought about a revision of tactics from the old spectacular passing movements and brilliant individualism, to the thrilling "three-kick" raids on goal and team-work; from frills to thrills. Many people will say it was a change for the worse. But after all, it is what the public wants nowadays. They pay the piper so they should call the tune. The change certainly brought the end of the old style. New methods were required and Arsenal were the first to exploit them... Mr Chapman called upon me to outline the scheme I had in mind. I said I not only wanted a defensive centre-half but also a roving inside-forward, like a fly-half in rugby, to act as link between attack and defense. He was to take up such positions in mid-field that any defender would be able to give him the ball without the chance of an opponent intercepting it. Of course, I had in mind that I would be the forward proposed for this job. First we thrashed out the position of the centre-half. He was not to be a "policeman" to the opposing centre-forward. He was given a beat of a certain area bordering the penalty-line which he was to guard. The other defenders were to range themselves around him according to the direction of play. It was the beginning of Arsenal's "defense in depth" policy, brought almost to perfection by later teams. Then the roving forward was discussed. I got a surprise when I was told emphatically that I was not the man. Mr. Chapman said: "We want you up in attack scoring goals. You have the height and the stamina.' We talked about other players until Mr. Chapman said: "Well, it's your plan, Charlie, have you any suggestions to make?" Then it occurred to me that I had seen, in practice games and playing for the second team, an inside-forward who was likely to fill the role. He was Andy Neil, a Scot who was getting on in years but who could kill a ball instantly and pass accurately. So I said: "Yes, I suggest Andy Neil as the right man. He has a football brain and two good feet." Finally, after a lot of argument, it was decided that Neil should be the first schemer-in-chief. And I must say he made a very good job of it for nearly the rest of that season. Thus the Arsenal plan was brought into existence. It has been copied by most clubs. (12) Eddie Hapgood, Football Ambassador (1945) After a dozen games, Bill Collier, the Kettering manager, called me into his office and introduced me to a chubby man in tweeds, whose spectacles failed to hide the shrewd, appraising look from his blue eyes. I didn't know it then, but I was to see this man many times before he died so tragically seven years later. "Eddie, this is Mr. Herbert Chapman, the Arsenal manager," said Bill Collier. "And the other gentleman is Mr. George Allison." And so I met two of the men who were to play such a major part in my future football career. Herbert Chapman didn't say anything for a few seconds, then shot out, " Well, young man, do you smoke or drink?" Rather startled, I said, "No, sir." "Good," he answered. "Would you like to sign for Arsenal" Would I. I could hardly set pen to paper fast enough. I believe Mr. Chapman paid Kettering roughly £1,000 for my transfer - £750 down and a guarantee of about £200 for a friendly match later on. But I didn't worry about that at the time. That remark of Mr. Chapman's about smoking and drinking impressed itself on my mind, for I have never done either during my career, with the exception of drinking occasional toasts at banquets and other functions. (13) Matt Busby, Soccer at the Top - My Life in Football (1973) Men of stature really have their own effect on football by doing something different when something different is needed. The sheep follow, until some other man of stature leads them along a different path his adventurous, probing mind has charted. Such an adventurer was Herbert Chapman, who in transforming Arsenal transformed the game of football. Chapman was an adventurer who had caution as his watchword. I do not mean that he was cautious with money - well not with Arsenal's money at any rate. He took Huddersfield Town to two successive championships and then in 1925 joined Arsenal, whereupon he paid Sunderland £2,000 plus £100 per goal for Charlie Buchan, who proceeded to score twenty-one goals that season, nineteen in the League, two in the Cup, and Arsenal were beaten for the championship only by Huddersfield, who thereby made it a hat-trick of titles. That was adventurous enough, and so it was when Chapman lashed out the considerable fees for those days of nearly £1,000 for Bolton Wanderers' David Jack, and £9,000 for Preston North End's Alex James. But the most revolutionary move was the cheapest and simplest. Chapman (using an idea of Buchan's, it was said) evolved the third-back game around the solid Herbie Roberts, and thus ended the roving commission and the more adventurous play of centre-halves. The gentleman with the No. 5 on his back became thereafter a stopper rather than a stopper-starter-wanderer, almost stationary in the middle of the backs or behind them. The idea, wildly exaggerated now by adding a few more backs, was patently to keep at least the point you start off with. That was the cautious Chapman. The other clubs throughout the game, sooner or later, followed suit. Their problem was that they hadn't an Alex James, a David Jack, a Cliff Bastin or a Joe Hulme, to name only four, and I have said my piece about the James man and the James plan. Chapman bought the players to suit his ideas. He was more a visionary than a coach. If he wasn't a coach as modern coaches go he had what could be more use to some modern coaches than their obsession with numbers and plans. He was inspiring. He was persuasive. He could persuade a player how he could be the greatest at a certain job. He persuaded Alex James to be the great provider from the middle. Herbert Chapman died in 1934, but the results of his inspiring leadership and his building are shown by Arsenal's five championships between 1930 and 1938 (three in succession) and their FA Cup wins in 1930 and 1936. Those who followed him were bound to be haunted by his ghost. (14) Cliff Bastin, Cliff Bastin Remembers (1930) This Arsenal team of 1930-31 was the finest eleven I ever played in. And, without hesitation, I include in that generalization international teams as well. Never before had there been such a team put out by any club. (15) Phil Soar and Martin Tyler, The Official Illustrated History of Arsenal (2007) In 1932-33 Bastin and Hulme scored 53 goals between them, perfect evidence that Arsenal did play the game very differently from their contemporaries, who tended to continue to rely on the wingers making goals for the centre-forward, rather than scoring themselves. By playing the wingers this way, Chapman was able to have one more man in midfield, and thus control the supply of the ball, primarily through Alex James. But it was only possible because both wingers were exceptional footballers - Hume because of his speed and Bastin because of his tactical brain and coolness. (16) Stephen Studd, Herbert Chapman: Football Emperor (1981) Meetings were held each week to discuss both the previous game and the tactics to be used in the next. With Chapman presiding, every player was encouraged to express his own opinion. This was something entirely new in football, a marked contrast to the prevailing easy-going system where players were left to work out their own tactics. In holding the talks Chapman was asking his players to contribute to a joint effort, to become more involved with each other as a unit. It was an appeal to intelligence as well as physical skill, and it had the effect of boosting self-respect, fostering a sense of loyalty, and raising a player's status above that of a mere paid servant. (17) Richard Whitehead, The Times (23rd October, 2004) James also arrived in North London in headline-making circumstances, but only after a prolonged Nicolas Anelka-like sulk had ensured his departure from Preston North End. James was keen to earn more than the £8-a-week maximum wage, but the only way for Arsenal to circumvent the Football League’s strict regulations was for their signing to take up additional employment as a “sports demonstrator” at Selfridge’s on the impressive salary of £250. He was not an instant success — one sarcastic fan sent him a pair of battered child’s football boots with an accompanying note suggesting “it doesn’t matter much what you wear anyhow” — but James quickly became the brains behind a team that dominated domestic football in a fashion that had not previously been seen. Lying deeper than conventional inside forwards, he would spring Arsenal’s rapid breakaways from defense — a tactic that earned them the tag “lucky Arsenal” from disgruntled opposing fans who had frequently seen their team dominate territorially for no tangible reward. That tactic demonstrated the quality the little man with the commodious shorts shared most with his modern-day counterpart — the ability to hit passes so stunningly beautiful that they could adorn the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. (18) Barney Ronay, The Guardian (16th August, 2007) For the first 40 years or so of professional football there was no real concrete idea of what a manager actually did. Teams were picked by an ad-hoc committee of board members and the secretary-manager, a vaguely clerical figure with a distinctly below-stairs status. Herbert Chapman is credited with pioneering the modern notion of a manager as the dominant personality within a football club, first at Huddersfield and then at Arsenal in the 1920s and 1930s. An avuncular, silk-hatted figure, Chapman also pretty much invented the idea of tactics, floodlights and marketing and public relations, having successfully lobbied to have Gillespie Road tube station renamed Arsenal in 1932. |

| +-+ BACK TO TOP +-+ | |